William McMaster Murdoch

Lieutenant William McMaster Murdoch | |

|---|---|

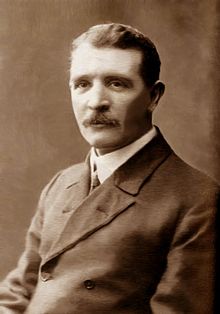

Murdoch in 1911 serving as First Officer on RMS Olympic | |

| Born | 28 February 1873 Dalbeattie, Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 39) |

| Other names | Will Murdoch |

| Education | Dalbeattie High School |

| Occupation | Ship's First Officer |

| Spouse |

Ada Banks (m. 1907) |

| Notes | |

William McMaster Murdoch, RNR (28 February 1873[1] – 15 April 1912) was a British sailor who served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Reserve and was the first officer on the RMS Titanic. He was the officer in charge on the bridge when the Titanic collided with an iceberg, and was amongst the 1,500 people who died when the ship sank.[2] The circumstances of his death have been the subject of controversy.

Early life

[edit]Murdoch was born in Dalbeattie in Kirkcudbrightshire (now Dumfries and Galloway), Scotland, the fourth son of Captain Samuel Murdoch, a master mariner, and Jane Muirhead, six of whose children survived infancy. The Murdochs were a long and notable line of Scottish seafarers; his father and grandfather were both sea captains as were four of his grandfather's brothers.

Murdoch was educated first at the old Primary School in High Street, and then at the Dalbeattie High School in Alpine Street until he gained his diploma in 1887. Finishing schooling, he followed in the family seafaring tradition and was apprenticed for five years to William Joyce & Coy, Liverpool, but after four years (and four voyages) he was so competent that he passed his second mate's Certificate on his first attempt.

Career

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]

He served his apprenticeship aboard the Charles Cosworth of Liverpool, trading to the west coast of South America. From May 1895, he was First Mate on the St. Cuthbert, which sank in a hurricane off Uruguay in 1897. Murdoch gained his Extra Master's Certificate at Liverpool in 1896, at age 23.

An officer of the Royal Naval Reserve, he was employed by the White Star Line in 1900. From 1900 to 1912, Murdoch gradually progressed from Second Officer to First Officer, serving on a succession of White Star Line vessels, Medic (1900, along with Charles Lightoller, Titanic's second officer), Runic (1901–1903), Arabic (1903), Celtic (1904), Germanic (1904), Oceanic (1905), Cedric (1906), Adriatic (1907–1911) and Olympic (1911–1912).

During 1903, Murdoch finally reached the stormy and glamorous North Atlantic run as Second Officer of the new liner Arabic. His cool head, quick thinking and professional judgement averted a disaster when a ship was spotted bearing down on the Arabic at night. His superior, Officer Fox, had ordered for the ship to steer "hard-a-port," but Murdoch rushed into the wheelhouse, brushed aside the quartermaster, and held the ship on course. The two ships barely missed each other by inches.

RMS Olympic

[edit]

The final stage of Murdoch's career began in May 1911, when he joined the new RMS Olympic, at 45,000 long tons (46,000 t). Not long before, he had shaved his moustache, apparently at his wife's prodding. Intended to outclass the Cunard Line ships in luxury and size, it needed the most experienced large-liner crew that the White Star Line could find. Captain Edward J. Smith assembled a crew that included Henry Wilde as Chief Officer, Murdoch as First Officer, and Chief Purser Hugh McElroy. On 14 June 1911 Olympic departed on her maiden voyage to New York, with a planned arrival on 21 June.

On 20 September 1911, the Olympic collided with the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke, badly damaging her hull. Since Murdoch was at his docking-station at the stern - a highly responsible position – he appeared at the incident inquiry and gave evidence. The collision was a major financial loss for the White Star Line as the voyage to New York was abandoned and the ship returned to Belfast for repairs, which took six weeks.

Murdoch returned to the Olympic on 11 December 1911, serving in that capacity until March 1912. During that time, there were two further, though lesser, incidents, striking a sunken wreck and needing to have a broken propeller replaced, and nearly running aground while leaving Belfast. Upon arriving in Southampton, Murdoch learned that his next assignment would be the Chief Officer of the Titanic, the Olympic's sister ship, serving under Captain Edward J. Smith. Charles Lightoller later wrote that "three very contented chaps" headed north to Belfast, for he had been appointed First Officer, and their friend David Blair was set to be Second Officer. Awaiting them would be Joseph Groves Boxhall, as Fourth Officer, who had worked with Murdoch on the Adriatic.

RMS Titanic

[edit]

Murdoch, with an "ordinary master's certificate" and a reputation as a "canny and dependable man", had climbed through the ranks of the White Star Line to become one of its foremost senior officers. Murdoch was originally given the title Chief Officer for RMS Titanic's maiden voyage. On March 27, 1912, the ship's four junior officers came aboard and reported to Murdoch. Murdoch ordered Fifth Officer Lowe and Sixth Officer Moody to inspect the starboard-side lifeboats and to make sure their equipment was complete; he ordered Third Officer Pitman and Fourth Officer Boxhall to do likewise with the port-side lifeboats. However, almost as soon as the ship had tied up in Southampton, the captain, Edward Smith, brought Henry Wilde in as his Chief Officer (from a prior assignment), so Murdoch became the First Officer. Charles Lightoller was in turn reduced to Second Officer, and the original Second Officer, David Blair, would not sail with Titanic at all. When the ship began her maiden voyage on 10 April, Murdoch was on the Poop Deck, in charge of the mooring lines, being assisted by Third Officer Pitman. As the ship went out into the Atlantic, Murdoch took the 10:00-2:00 watches every mid-day and night. It was his responsibility to draw up the list of boat assignments, and he followed through on this promptly after departing Southampton.

On 14 April 1912, Murdoch had the 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. watch on the bridge. However, the officers' lunch was served at 12:30. Lightoller returned to the bridge at that time to relieve Murdoch and let him grab a quick bite to eat. Murdoch did not return until 1:00–1:05 p.m.. When Murdoch returned from his lunch, Lightoller mentioned that Captain Smith had given him a message regarding ice. Murdoch showed no overt surprise, but Lightoller was under the impression that the subject was new to the First Officer, just as it had been to him.[3] Dinner for the officers was served at 6:30 p.m. in the Officers' Mess. Murdoch, then off duty, had taken the opportunity to have his meal. Then he headed up to the bridge, arriving at 7:05 p.m.. Upon arrival, he took the watch for a half-hour so that Lightoller could have his own dinner. At about 7:15, Lamp Trimmer Samuel Hemming arrived on the bridge and reported to Murdoch that all the lights had been set for the evening. Murdoch told him to get "the fore-scuttle hatch closed, there is a glow left from that, as we are in the vicinity of ice, and I want everything dark before the bridge." Murdoch was keenly aware that ice was near, and he was being particularly careful to ensure that nothing interfered with the night vision of the lookouts and officers. Lightoller returned from dinner to resume his watch. Murdoch remarked to him that the temperature had dropped another four degrees. Murdoch departed the bridge, and later relieved Lightoller at 10:00 p.m.. Lightoller conveyed to Murdoch the ship's course and the ice field that they were approaching, and that they expected to be in the vicinity of the ice somewhere around 11:00. Lightoller wished Murdoch "joy of his Watch" and departed the bridge.[4]

At approximately 11:39 pm on 14 April 1912, First Officer Murdoch was in charge when a large iceberg was sighted directly in the Titanic's path. Lookout Fredrick Fleet rang the warning bell three times. It is likely that Murdoch had already seen the iceberg, and as soon as Officer Moody relayed Fleet's warning, "Iceberg right ahead!", Murdoch "rushed" from the bridge wing to the bridge. Quartermaster Robert Hichens, who was at the helm, and Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, who had heard the warning bell and had come from the officers' quarters behind the bridge, heard Murdoch's order to turn the helm[5] "Hard-a-starboard",[6][7][8] a tiller command which would turn the ship to port (left) by moving the tiller to starboard (right). At the time, steering instructions on British ships generally followed the way tillers on sailing vessels are operated, with turns in the opposite direction from the commands. As Walter Lord noted in The Night Lives On, this did not fully change to the "steering wheel" system of commands in the same directions as turns until 1924. This has led to rumours that Murdoch's orders were misinterpreted by the helmsman, resulting in a turn the wrong way.[9]

Fourth Officer Boxhall testified that Murdoch set the ship's telegraph to "Full Astern", but Greaser Frederick Scott and Leading Stoker Frederick Barrett testified that the stoking indicators went from "Full" to "Stop".[10] During or immediately before the collision, Quartermaster Alfred Olliver (who was walking on to the bridge during the collision) testified that he heard Murdoch give the order "Hard a'port"[11] (moving the tiller all the way to the port (left) side turning the ship to starboard (right)) in what may have been an attempt to swing the aft section of the ship away from the iceberg in a manoeuvre called a "port around"[12] (this could explain his comment to the captain "I intended to port around it"). The fact that this manoeuvre was executed was supported by other crew members who testified that the stern of the ship never hit the iceberg.[13] The orders that Murdoch gave to avoid the iceberg are debated. According to Oliver, Murdoch ordered the helm "hard to port" to ward off the stern of the iceberg. Hichens and Boxhall made no mention of the order. However, since the stern avoided the iceberg, it is likely that the order was given and carried out.[14][15]

Despite these efforts, the ship made its fatal collision about 37 seconds[16] after the iceberg had been sighted, opening the first six compartments.[17] After the collision, Murdoch raced towards the watertight door controls, in the open bridge, and signalled the alarm below. Murdoch then told quartermaster Olliver to "take the time, and told one of the junior officers to make a note" in the logbook. Captain Smith came on to the bridge, asking Murdoch "What have we struck?" Murdoch told what happened and affirmed that the watertight doors were shut and the warning bell had rung. Smith, Murdoch and Boxhall walked out on to the starboard bridge wing, trying to spot the iceberg.

Murdoch was put in charge of the starboard evacuation, during which he launched ten lifeboats. Seaman Buley remembered an order from Murdoch for the "seamen to get together and uncover the boats and turn them out as quietly as though nothing had happened". Pitman joined Murdoch in helping and was ordered to start working on Boat No. 5. Murdoch was hard at work on Boat No. 7; when lookout George Hogg worked with him, Murdoch told him to step into the boat. Murdoch ordered Steward Etches to get into Boat No. 5 and assist the men with the forward fall. Murdoch told Pitman to take charge of the boat. He shook his hand and said, "Goodbye, good luck to you." Pitman, who at that time did not expect the ship to sink, later felt that Murdoch had not expected to see him again. Lightoller later recalled that Wilde had apparently talked to Murdoch about where the firearms were, but Murdoch had no clue where they were, due to the re-shuffling of senior officers at Southampton. Lightoller led Wilde, Smith and Murdoch to the cabin, where he brought out the box of revolvers.[18] Murdoch placed able-bodied seaman George Moore in charge of Boat. No. 3. He then began working at Lifeboat #1, where he allowed Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon; his wife Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon; her secretary, Mabel Francatelli; Abraham Salomon; and C. E. Henry Stengel to get in. As Stengel climbed in, he rolled over the teak top-rail and into the boat. Murdoch laughed heartily, saying, "That is the funniest sight I have seen to-night." At Boat No. 9, Murdoch, a number of stewards and other members of the victually department were passing women and children over from the port side to fill up the boat. He fired warning shots at Collapsible C during the loading process in order to prevent a group of men swarming the Collapsible.[19] Murdoch perished in the disaster and his body was never recovered.[20]

Personal life

[edit]Family and marriage

[edit]

In 1903, Murdoch met a 29-year-old New Zealand school teacher named Ada Florence Banks en route to England on either the Runic or the Medic. They began to correspond regularly. On 2 September 1907 they were wed in Southampton at St Denys Church. The marriage register entry was witnessed by Captain William James Hannah and his wife, and the addresses given by the bride and groom suggest they were lodging with the Hannahs. Captain Hannah came from a family of seafarers with roots in Kircudbrightshire like Murdoch, and was Assistant Marine Superintendent for the White Star Line at Southampton. Hannah would see Murdoch for the last time when he witnessed the testing of lifeboats before Titanic departed from Southampton on 10 April 1912.[21]

Death

[edit]Several eyewitnesses, including Third Class Passenger Eugene Daly and First Class passenger George Rheims, claimed to have seen an officer shoot one or two men during a rush for a lifeboat, then shoot himself.[22] It was rumoured that Murdoch was the officer.[22]

In a letter to Murdoch's widow, Second Officer Lightoller denied the rumours, writing that he saw Murdoch working on the falls to Collapsible A when he was swept overboard when the ship began her final plunge.[23] However, Lightoller's testimony at the U.S. inquiry suggests that he was not in a position to witness Murdoch being swept overboard. It is also possible that Lightoller may have wanted to conceal the suicide, if it occurred, from Murdoch's widow. Later in life, according to a family friend, Lightoller reportedly admitted that someone did die by suicide in the disaster. Additionally, James O. McGiffin, son of Captain James McGiffin (a close personal friend of Murdoch), said that Lightoller had told his father that Murdoch had shot a man.[23]

An officer's suicide was portrayed in the 1996 miniseries Titanic and the 1997 film Titanic each portraying Murdoch as the participant.[22] When Murdoch's nephew Scott saw the 1997 film, he objected to the portrayal as damaging to Murdoch's heroic reputation.[24] Film executives later flew to Murdoch's hometown to apologize.[25] The film's director, James Cameron, said that the depiction was not meant to be negative, and added, "I'm not sure you'd find that same sense of responsibility and total devotion to duty today. This guy had half of his lifeboats launched before his counterpart on the port side had even launched one. That says something about character and heroism."[26][27]

Author Tim Maltin writes that, although the evidence is circumstantial, "it does seem that an officer did shoot himself and Murdoch seems the most likely candidate. As Titanic experts Bill Wormstedt and Tad Fitch point out, Murdoch was the man directly in charge of the ship in the hours leading up to the collision with the iceberg and he was therefore responsible for the ship and all its passengers during that time. His career at sea was effectively over, even if he survived the disaster".[28]

Legacy

[edit]

Shortly after the sinking of the Titanic, the New York Herald published a story about Rigel, a dog reportedly owned by Murdoch who saved some of the survivors from the sinking.[29] While the story was widely reproduced, contemporary analyses cast doubt on whether the dog actually existed.[30]

In Murdoch's hometown of Dalbeattie, a memorial fund was created for the High School.[31] Residents of the town objected to the depiction of Murdoch in the 1997 film Titanic and requested an apology. In April 1998, representatives from the film studio Twentieth Century Fox presented a £5,000 cheque for the memorial fund, but did not offer a formal apology.[32] The film's director, James Cameron, said that his depiction of Murdoch was not meant to be negative. In 2004, he tentatively said that "it was probably a mistake" to portray a specific person and could understand the family's objections.[32][33]

In April 2012, Premier Exhibitions announced that it had identified Murdoch's belongings from a prior expedition to the wreck of the Titanic in 2000. There was a toiletry kit with Murdoch's initials embossed on it, a spare White Star Line officer's button, a straight razor, a shoe brush, a smoking pipe, and a pair of long johns.[34] The items were recovered by David Concannon, Ralph White and Anatoly Sagalevitch diving in the Russian submersible Mir 1 in July 2000.

Portrayals

[edit]- Theo Shall (1943) (Titanic)

- Barry Bernard (1953) (Titanic)

- Richard Leech (1958) (A Night to Remember)

- Paul Young (1979) (S.O.S. Titanic) (TV Movie)

- Stan Bocko (1989) (Pilots of the Purple Twilight) (A play by Steve Kluger)

- Malcolm Stewart (1996) (Titanic) (TV Miniseries)

- David Costabile (1997) (Titanic) (Broadway Musical)

- Ewan Stewart (1997) (Titanic)

- Courtenay Pace (1998) (Titanic: Secrets Revealed) (TV Documentary)

- Charlie Arneson (2003) (Ghosts of the Abyss) (Documentary)

- Noel Burton (2008) — The Unsinkable Titanic (Documentary)

- Brian McCardie (2012) (Titanic) (TV series/4 episodes)

- David McArdle (2016) (Pilots of the Purple Twilight) (A play by Steve Kluger)

References

[edit]- ^ Barczewski, Stephanie (2006). Titanic: A Night Remembered. London, UK: Hambledon Continuum. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-85285-500-0. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Walter Lord (1955), A Night To Remember, Penguin Books

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 118.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 126-136.

- ^ "Appendix II: STOP Command / "Porting Around" Maneuver". marconigraph.com. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall reported during the Enquiry that upon arriving on the bridge after the fact, he saw both telegraph handles pointing to FULL ASTERN, and heard Murdoch report that the engines had been reversed to Captain Smith. This, in effect, has led historians to believe that Murdoch rang down a 'crash stop.'

- ^ Nathan Robison (12 February 2002). "Hard a-starboard". Encyclopedia Titanica.

- ^ "Titanic Inquiry Project – United States Senate Inquiry". titanicinquiry.org.

- ^ "Testimony of Robert Hichens (Quartermaster, SS Titanic)". Titanic Inquiry Project - United States Senate Inquiry.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (21 September 2010). "Titanic sunk by steering blunder, new book claims". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "STOP Command / "Porting Around" Maneuver". marconigraph.com.

- ^ "STOP Command / "Porting Around" Maneuver". marconigraph.com.

- ^ ""Last Log of the Titanic" -Four Revisionist Theories – a "port around" or S-curve manoeuvre in which "the bow is first turned away from the object, then the helm is shifted (turned the other way) to clear the stern"". Archived from the original on 28 October 2003. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ^ "STOP Command / "Porting Around" Maneuver". marconigraph.com.

SENATOR BURTON: Do you not think that if the helm had been hard astarboard the bow would have been up against the berg? QUARTERMASTER GEORGE ROWE: It stands to reason it would, sir, if the helm were hard astarboard.

- ^ Mark Chirnside 2004, p. 155

- ^ Gérard Piouffre 2009, p. 140

- ^ "titanic-model.com, Titanic and the Iceberg – By Roy Mengot". Titanic-model.com. 14 April 1912. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "The whole impact had lasted only 10 seconds". Pbs.org. 10 April 1912. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 198-200.

- ^ Testimony of Hugh Woolner at the US Inquiry

- ^ Winocour 1960, p. 316.

- ^ "Titanic and Transport Memorabilia Sale on Saturday 20th April 2013. Lot 212". henry-aldridge.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

R.M.S. TITANIC: CAPTAIN MAURICE CLARKE ARCHIVE. Typed notes dated April 28th 1912 relating to the Board of Trade enquiry into Titanic. The notes detail Captain Clarke's inspection into the lifeboats. "On the morning of sailing Wed 10th April, I gave instructions to the Chief Officer after The Board of Trade muster, to swing out No's 4 and 15 lifeboats which were situated on the starboard side of boat deck. The two boats were swung out one at a time. The time occupied the covers and grips on being 3¼ and 3½ minutes this being checked by Captains Steel and Hannah, the two marine Superintendents. All worked most satisfactorily, the crews were exercised by their officers and were fully satisfied as to the crew's efficiency."

- ^ a b c On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the R.M.S. Titanic (Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton and Bill Wormstedt), Appendix K: "Shots in the Dark: Did an Officer Commit Suicide on the Titanic?", ISBN 1848689276), pg. 305.

- ^ a b "Charles Herbert Lightoller- William Murdoch".

- ^ "Nephew angered by tarnishing of Titanic hero". BBC News. 24 January 1998. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Titanic makers say sorry". BBC News. 15 April 1998.

- ^ James Cameron’s Titanic, p. 129.

- ^ "Murdoch". williammurdoch.net. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ 101 Things You Thought You Knew About the Titanic - But Didn't! at Google Books.co.uk

- ^ "Did Murdoch Have a Heroic Dog Named 'Rigel'?". williammurdoch.net. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Maltin & Aston 2011, p. 176.

- ^ "MURDOCH MEMORIAL PRIZE". Encyclopedia Titanica. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b "The Dalbeattie Apology | William Murdoch". www.williammurdoch.net. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "BBC News - Titanic director's degree award". 20 July 2004.

- ^ Prengaman, Peter (3 April 2012). "AP Exclusive: Titanic artifacts linked to officer". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- William McMaster Murdoch, A Career at Sea. By Susanne Störmer

- Encyclopedia Titanica

- Dalbeattie museum

Bibliography

[edit]- Bruce Beveridge (2009). Titanic, the ship magnificent. Vol. two: interior design & fitting out. The History Press. p. 509. ISBN 9780752446264.

- Daniel Allen Butler (2009). The other side of the night: The Carpathia, the Californian and the night the Titanic was lost. Casemate Publishers. p. 254. ISBN 978-1935149026.

- Mark Chirnside (2004). The Olympic-class ships : Olympic, Titanic, Britannic. Tempus. p. 349. ISBN 0-7524-2868-3.

- Maltin, Tim; Aston, Eloise (2011). 101 Things You Thought You Knew About the Titanic . . . but Didn't!. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-55893-5.

- Gérard Piouffre (2009). Le " Titanic " ne répond plus (in French). Larousse. p. 317. ISBN 9782035841964.

- Fitch, Tad; Layton, J. Kent; Wormstedt, Bill (2012). On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the R.M.S. Titanic. Amberley Books. ISBN 978-1848689275.

- Winocour, Jack, ed. (1960). The Story of the Titanic as told by its Survivors. London: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-20610-3.

External links

[edit]- Dalbeattie Town History – Murdoch of the 'Titanic'

- Murdoch -The Man, the Mystery

- William McMaster Murdoch at Find a Grave

- William McMaster Murdoch Archived 6 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine: Women and Children First Order